With flood insurance overhaul stalled in Congress, FEMA moves to tweak program on its own

WASHINGTON — The Federal Emergency Management Agency is making a handful of tweaks to the National Flood Insurance Program to inject more private money into the government-dominated flood insurance market.

Officials at FEMA plan to loosen rules around private insurers offering their own flood policies and have taken on nearly $1.5 billion in reinsurance from more than two dozen companies to help offset potential future losses, the agency announced this week.

The administrative moves bypass Congress, where lawmakers have been deadlocked for months over how to overhaul the NFIP, which is drowning in red ink.

The tweaks come as the program, already roughly $30 billion in debt, continues to pay out claims from a series of destructive hurricanes in 2017 and prepares for the upcoming hurricane season, which forecasters have warned could bring another spate of powerful storms.

The NFIP took out reinsurance coverage — a backstopping policy for insurers that pays out if covered losses exceed a certain threshold — in 2017. Those policies ended up covering around $1 billion in claims from NFIP policyholders in the Houston area after Hurricane Harvey in August.

The program will pay fees to more than two dozen reinsurance companies this year for additional coverage. That could cost the program money if few floods in the coming year lead to only minimal claims — but it’ll also limit the blow from to the program from another catastrophic season.

If claims to the NFIP top $4 billion, the reinsurance coverage will kick in to cover the next $1.46 billion in losses, FEMA said in a news release.

The two other significant changes unveiled by FEMA drew mixed reactions from insurers, policyholder advocates and Louisiana lawmakers.

FEMA is dropping its ‘non-compete’ rule that had barred insurance companies that sell NFIP-backed policies through the NFIP’s “Write Your Own” program from offering their own flood insurance coverage. That potentially will entice more insurance companies to offer their own products.

At the same time, “Write Your Own” companies will see the cut the NFIP pays them for selling policies trimmed back slightly, a move that could either result in lower premiums for policyholders or send more money to the NFIP to pay claims.

Roy Wright, the FEMA official who runs the NFIP, told POLITICO in an interview that opening up the flood-insurance market to more private competition would benefit federal taxpayers by hopefully reducing the number of homeowners who go without coverage.

“We need more people selling these products,” Wright said.

Insurance industry groups mostly welcomed FEMA’s moves to free “Write Your Own” companies to sell their own policies — a step the industry has long pushed for — and adding reinsurance coverage, though industry representatives worried that cutting compensation for companies that sell NFIP policies could lead to fewer sales.

“The flooding events in 2016 and 2017 clearly show that too few property owners purchase flood coverage,” said Tom Santos, vice president for federal affairs for the American Insurance Association. “Thus, we ought to be looking for ways to expand consumer options by preserving and expanding the private sector’s ability to offer flood insurance coverage — both NFIP coverage and private coverage.”

Members of Congress have mulled both policy changes for years.

Sen. John Kennedy, R-Louisiana, has proposed a much steeper cut to the share of NFIP revenue “Write Your Own” companies could keep in legislation he wrote with Sen. Bob Menendez, D-New Jersey.

Fellow Louisiana Republican Sen. Bill Cassidy, who’s backing his own flood-insurance bill with New York Democratic Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, has also backed trimming compensation to “Write Your Own” companies as a way to pull more money into the program.

Louisiana Republicans have generally supported the idea of allowing more private insurance companies to sell flood policies to homeowners. But Louisianans and other coastal lawmakers worry that private companies could “cherry-pick” the NFIP, poaching the most profitable policies while leaving the federal government with the riskiest and most heavily subsidized properties.

A large number of NFIP policyholders, including many Louisianans, pay below-market rates because of “grandfathering” rules that can leave the premiums on an older property artificially low even if FEMA later determines its risk of flooding has risen.

Among the concerns is that “Write Your Own” companies could use their access to the NFIP’s extensive and detailed database of flood history and past claims to strategically undercut the federal program on rates. The NFIP’s data, including details on past claims for each property in the program, give it a huge potential advantage over private competitors in determining a property’s future risk of flooding.

The FEMA regulations prohibit “Write Your Owns” from using NFIP data in calculating or marketing their non-NFIP policies. In theory, that should help protect the NFIP from being aggressively undercut by advantaged competitors, said Caitlin Berni, vice president of policy and communications for Greater New Orleans Inc. who also leads a national coalition to lobby on flood insurance issues.

“We need more people covered for flood risk and I don’t think, given how FEMA has made the change and constraints of current law, that cherry-picking will become a significant issue,” Berni said.

Cassidy’s proposed NFIP overhaul would have essentially created a pilot program allowing private insurers to compete directly against the NFIP only in certain segments of the market. Under the Cassidy-Gillibrand proposal, private competitors could have paid the NFIP to access the program’s historical loss data.

Rapidly hiking premiums on those properties — as some budget hawks who’ve criticized the NFIP as fiscally unsustainable have proposed — could tank home values and wipe out equity.

U.S. Rep. Garret Graves, R-Baton Rouge, said he supports the idea of encouraging the private market to cover more flood risk and hoped insurers eventually begin offering “all hazard” policies that cover flood damage on top of wind, fire and other normal lines.

But Graves said in an interview last week that FEMA should have left changes to the NFIP to Congress. Making piecemeal changes to the program, Graves added, could also undermine efforts to hammer out a broad-ranging deal on the future of the program.

“I think it’s problematic for Louisiana and for a long-term fix of the flood insurance program,” Graves said of the administrative changes.

The U.S. House of Representatives passed its own proposed overhaul of the NFIP in December after House Majority Whip Steve Scalise, R-Jefferson, brokered a compromise with House Financial Services Chairman Jeb Hensarling, a Texas Republican and hardline budget hawk who’s pressed for major rate-hikes for policyholders that could hit Louisiana hard.

That bill also included a larger cut to the compensation for “Write Your Own” companies than FEMA is implementing administratively. It split Louisiana’s congressional delegation, half of whom backed it and half of whom — including Graves — blasted it as potentially devastating to homeowners in the state.

Scalise, the House’s No. 3 Republican, embraced some of the policies FEMA rolled out in a statement Friday.

“Exploring creative ways to reform NFIP will be necessary as we work toward a long term reauthorization of the program,” Scalise said, “and this includes reinsurance, engaging the private sector in flood insurance and more accurate mapping for areas like south Louisiana, where for so long FEMA has gotten it wrong.”

But Scalise also vowed to protect homeowners with below-market “grandfathered” rates in any long-term deal on the NFIP “so that people who played by the rules aren’t penalized or kicked out of the program.”

The Senate isn’t expected to take up the House-passed bill, in part because of objections from senators from Louisiana and other flood-prone areas, who have prioritized affordable premiums for homeowners when considering changes to the program.

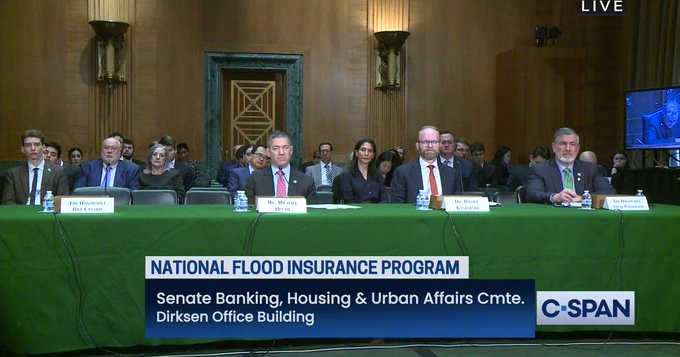

The Senate’s Banking Committee, which oversees the program, has also been tied up with work on a major, unrelated effort to rollback parts of the Dodd-Frank set of banking regulations imposed after the 2008 financial crisis.

Just when Capitol Hill lawmakers will get to serious negotiations on the NFIP’s future remains unclear. The program has hobbled along on a series of short-term extensions since expiring at the end of September and key negotiators remain far apart on how to handle the program in the future.

Sharp disagreements over the future role of the private market in flood have played a significant role holding up a long-term deal on the program.

It’s too soon to tell whether FEMA’s administrative move — which doesn’t go as far as some free-market advocates have pushed for — might break up that logjam and clear the way for a deal.

To read the full article click here.